Monica Stroe

The market for body care services in Bucharest (sports halls, spas) addresses a need to support ones’s body to become “a personal affirmation, a mode to stress an aesthetics and a set of morals” (LeBreton 2009: 294). The visuals and the motivational quotes that adorn or advertise two fitness centres in Bucharest seem to indicate a strategic declination of body care services into personal development services.

The market for body care services in Bucharest (sports halls, spas) addresses a need to support ones’s body to become “a personal affirmation, a mode to stress an aesthetics and a set of morals” (LeBreton 2009: 294). The visuals and the motivational quotes that adorn or advertise two fitness centres in Bucharest seem to indicate a strategic declination of body care services into personal development services.

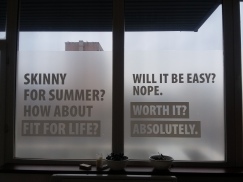

One fitness hall in northern Bucharest posts mentoring messages on its walls and windows, that divert the focus from the training of the body to the training of the mind. The practicing of fitness is portrayed as an all-transforming experience with a higher meaning: “Skinny for summer? How about fit for life?”; “Will it be easy? Nope. Worth it? Absolutely.”; “Know your limits but never stop trying to exceed them”. The key words that complete the motivational props borrow mantra-terms from the corporate language: performance, team, success, progress.

The poster of a chain of fitness halls typically positioned in the proximity of office clusters or inside upscale hotels, named – revealingly – World Class, presents a manager in his prime (30 y.o.) in an active pose (working out using a fitness machine). He describes himself as “100% willpower” and invites his audience to transform their lifestyle by becoming a member of the gym. The chain’s proposed programme (branded as Lets go you TM) is a promise of a multidimensional – and personalised – control of the self that includes – according to the poster – a nutritional plan, a training programme, as well as “motivation and monitoring”, which one can reasonably assume is overseen by a personal trainer.

The focus on self-mobilisation, transformation, becoming, progressing etc. recalls the endless race discussed by LeBreton “which proposes adhering to oneself, to an ephemeral identity, which is nonetheless essential at a certain point in time. These tyrannies of appearance request a continuous work to address the self” (LeBreton 2009: 295). The quest for control and discipline over the body and the mind instead of a quest for beauty draws the practices of keeping in shape closer to personal development goals.